The Path to Achieve Ultra-Low Inference Latency With LLaMA 65B on PyTorch/XLA

Background & State of the Art

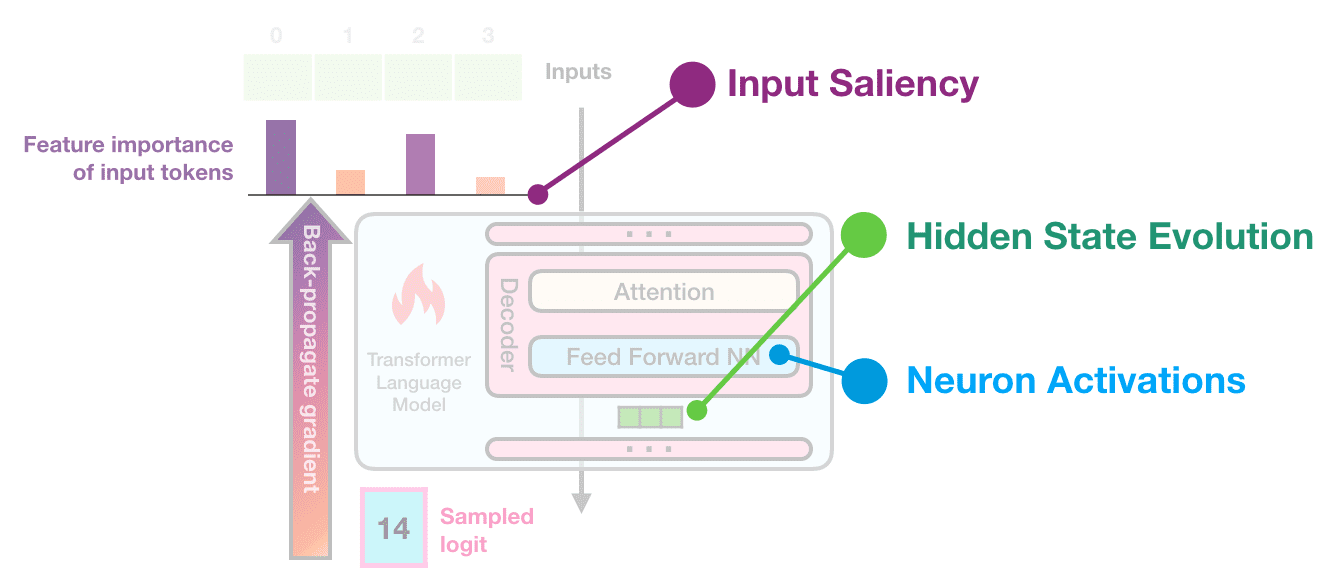

In the natural language processing (NLP) space, language models are designed to generate a token (e.g. word) using a sequence of past input tokens. Large Language Models (LLMs) are the latest deep learning innovation in this space built to generate text in a human-like fashion. These models generally use transformers to improve their attention over a large sequence of input tokens.

LLaMA, open sourced by Meta AI, is a powerful foundation LLM trained on over 1T tokens. LLaMA is competitive with many best-in-class models such as GPT-3, Chinchilla, PaLM. LLaMA (13B) outperforms GPT-3 (175B) highlighting its ability to extract more compute from each model parameter.

In this blog post, we use LLaMA as an example model to demonstrate the capabilities of PyTorch/XLA for LLM inference. We discuss how the computation techniques and optimizations discussed here improve inference latency by 6.4x on 65B parameter LLaMA models powered by Google Cloud TPU v4 (v4-16).

Model Overview

We demonstrate the performance capabilities of PyTorch/XLA on LLaMA, the latest LLM from Meta. We showcase performance optimizations on a series of common LLaMA configurations. Notice the 175B parameter model configuration is absent in the public domain. For the 175B parameter model mentioned below, we apply OPT 175B model configuration to the LLaMA code base. Unless stated otherwise, in all configurations, we use max_seq_len=256 and dtype=bfloat16 for weights and activations.

Table 1: Model Configurations Explored in this article

| LLaMA | Model Hyper Parameters | |||

| # Parameters | Dimensions | N Heads | N Layers | Max Seq Len |

| 7B | 4,096 | 32 | 32 | 256 |

| 33B | 6,656 | 52 | 60 | 256 |

| 65B | 8,192 | 64 | 80 | 256 |

| 175B | 12,288 | 96 | 96 | 256 |

Performance Challenges of LLMs

LLMs have a few properties that make them challenging for compiler optimizations. (a) LLMs use autoregressive decoding to generate the next token baked on the previous ones; this means prompt tensors and coaches have a dynamic shape. (b) LLMs must work with variable input prompt lengths without triggering recompilation due to input tensor shape changes; input tensors must be properly bucketized and padded to avoid recompilation. (c) LLMs often require more memory than a single TPU (or GPU) device can support. A model-sharding scheme is required to fit the model across a distributed compute architecture. For instance, a LLaMA model with 65B parameters can fit on a v4-16 Cloud TPU, which is comparable to 8 A100 GPUs. (d) running LLMs in production can be expensive; one way to improve performance per total cost of ownership (Perf/TCO) is via quantization; quantization can potentially reduce hardware requirements.

Inference Tech Stack in PyTorch/XLA

Our goal is to offer the AI community a high performance inference stack. PyTorch/XLA integrates with TorchDynamo, PjRt, OpenXLA, and various model parallelism schemes. TorchDynamo eliminates tracing overhead at runtime, PjRt enables efficient host-device communication; PyTorch/XLA traceable collectives enable model and data parallelism on LLaMA via TorchDynamo. To try our results, please use our custom torch, torch-xla wheels to reproduce our LLaMA inference solution. PyTorch/XLA 2.1 will support the features discussed in this post by default.

Parallel Computing

FairScale Sharding

LLaMA uses FairScale model sharding API (fairscale.nn.model_parallel.layers). We built an equivalent representation of this API using PyTorch/XLA communication collective (CC) ops such as all-reduce to communicate program state (e.g. activations) between accelerators. TorchDynamo does not fully support capturing CC ops currently (a.k.a. traceable collectives). Without this support, a TorchDynamo FX graph would be cut at every device communication, meaning at every model layer. Graph cuts lead to performance loss as the underlying XLA compiler loses full graph optimization opportunities. To resolve this, we offer PyTorch/XLA traceable collectives by integrating the dispatcher collectives into our existing CC APIs. The difference is we don’t need to insert c10d.wait() ops after collectives, given the lazy execution nature of PyTorch/XLA. With support for traceable collectives, PyTorch/XLA allows singular FX graph generation in TorchDynamo.

Autoregressive Decoding on PyTorch/XLA

LLMs need autoregressive decoding to feed the previous word as a prompt to predict the next token. Autoregressive decoding leads to unbounded dynamic shape problems, which in turn causes recompilation of every prompt. We optimized the LLaMA autoregressive decoder to operate with fixed shapes that in-place updates the KV-cache, output sequences, and attention masks during every token generation. With a combination of padding, masking, and index ops, we avoided excessive graph recompilation, thereby achieving efficient autoregressive decoding.

KV-Cache Optimization

LLaMA implements autoregressive decoding with KV-cache. For every generated token, the KV-cache stores the attention key/value activations of each Transformer layer. Thus, upon decoding a new token, the key/values of prior tokens no longer need recomputation.

In LLaMA, the KV-cache tensor slices are updated in-place; this leads to recompilation events every time a token is generated. To address this issue, we use index tensors and tensor.index_copy() ops to replace the in-place slice updates. Attention masks and output sequences also benefit from the same optimization.

Input Prompt Optimization

Variable length input prompts are common in LLM applications. This property causes input tensor shape dynamism and in turn recompilation events. When processing a prompt to fill the KV-cache, we either (a) process the input prompt token-by-token, or (b) process the whole prompt in one iteration. The pros and cons of each method are:

- Pre-compile 1 graph and process a prompt token-by-token

- Practical: 1 graph is compiled during warm-up

- Slow: O(L) to process an input prompt length L – a disadvantage for long prompts

- Pre-compile all graphs with input lengths ranging from 1 to max_seq_len (e.g. 2,048)

- Impractical: pre-compile and cache max_seq_len graphs during warm-up time

- Fast: 1 graph execution to process the full prompt

We introduce prompt length bucketization, an optimization to strike a balance between the two alternatives. We define a set of ascending bucket sizes, (b0,b1,b2,…,bB-1), and then pre-compile program graphs with input sizes according to these bucket values, (G0,G1,G2,…,GB-1); B is the number of buckets. For a given input prompt, we round up the prompt length to the closest bucket value bn, pad the sequence, and use Gn to process the prompt in one iteration. The computation on the padding tokens is discarded. For prompts larger than the largest bucket size, we process them section-by-section.

The optimal bucket sizes should be determined by prompt length distribution in a target application. Here, we adopt bucket lengths: 128, 256, 384, 512. Any input prompt with up to 2,047 tokens requires up to 4 graph executions. For example, a 1,500 input prompt with generation length of 256 requires 260 graph executions – 4 to process the input, and 256 to generate the output.

Quantization

Quantization reduces the number of bits necessary to represent a value; it reduces the bandwidth to communicate data across multiple accelerator nodes (via collectives) and lowers the hardware requirements to serve a specific model size.

Normally, with BF16 weights, a 175B parameter model would consume about 351GB of memory, and therefore require a v4-32 instance to accommodate the model. By quantizing the weights to INT8, we reduced the model size by roughly 50%, allowing it to run on a smaller v4-16 instance. Because LLaMA shards model activations, quantization offers negligible communication gain.

In our experiments, we quantized the linear layer. Since LLaMA model checkpoints are unavailable publicly, and our goal is to evaluate performance, the quantized model is initialized with random weights.Recent literature such as AWQ and Integer or Floating Point? offer insights into performance properties of LLaMA under various low-bit quantization schemes.

Effect of Batch Size on Quantization Performance

TPU v4 is programmed to run matmul on the Matrix Multiply Unit (MXU) when the model batch size (BS) > 1. For BS = 1, matmul runs on the Vector Processor Unit (VPU). Since MXU is more efficient than VPU, INT8 quantization gains performance at BS>1. See Performance Analysis section for details.

Op Support

Occasionally, new models introduce new mathematical operations that require PyTorch/XLA to extend its supported op set for compilation. For LLaMA, we supported: multinomial.

Methodology

LLaMA works on PyTorch/XLA out of the box on LazyTensorCore. We use this configuration as a baseline for our follow up analysis. All experiments assume 256-long input prompts. In the absence of a publicly available model checkpoint, we used random tensor initialization for this inference stack optimization effort. A model checkpoint is not expected to change latency results discussed here.

Model Sizing

Assuming N is the number of parameters, dimensions is the hidden size, n_layers is the number of layers, n_heads is the number of attention heads, the equation below can be used to approximate the model size. See the Model Overview section for details.

N = (dimensions)^2 * n_layers * 12

n_heads doesn’t affect N, but the following equation holds for the open sourced model configs.

dim = 128 * n_heads

Cache Sizing

Both model parameters and the cache layers in the Attention block contribute to memory consumption. Since the default LLaMA model uses BF16 weights, the memory consumption calculation in this section is based on BF16 weights.

The size of the cache layer is calculated by cache_size = max_batch_size * max_seq_len * dimensions. max_batch_size = 1 and max_seq_len = 256 are used as an example configuration in the following calculations. There are 2 cache layers in each Attention block. So, the total LLaMA cache size (in Bytes) is total_cache_size = n_layers * 2 * cache_size * (2 bytes).

TPU v4 Hardware Sizing

Each TPU v4 chip has 32GB of available High-Bandwidth Memory (HBM). Table 2 has the details on memory consumption and the number of required TPU chips to hold a LLaMA model.

Table 2: LLaMA TPU v4 HBM requirements (i.e. TPU v4 chip requirements)

| # Parameters | Parameter (MB) | Cache (MB) | Total (GB) | Min # of TPU v4 Chips |

| 7B | 14,000 | 134 | 14.128 | 1 |

| 33B | 66,000 | 408 | 66.41 | 3 |

| 65B | 130,000 | 671 | 130.67 | 5 |

| 175B | 350,000 | 1,208 | 351.21 | 11 |

Metrics

Below are useful metrics to measure inference speed. Assuming T is the total time, B is the batch size, L is the decoded sequence length.

Latency Definition

Latency is the time it takes to get the decoded result at target length L, regardless of the batch size B. Latency represents how long the user should wait to get the response from the generation model.

Latency = T (s)

Per-token latency

One step of autoregressive decoding generates a token for each sample in the batch. Per-token latency is the average time for that one step.

Per-token latency = T / L (s/token)

Throughput

Throughput measures how many tokens are generated per unit time. While it’s not a useful metric for evaluating online serving it is useful to measure the speed of batch processing.

Throughput = B * L / T (tokens/s)

To minimize confusion and misinterpretation, it’s better to avoid metrics like T / (B * L), which mixes latency and throughput.

Results

Figure 1 shows latency / token results for LLaMA 7B to 175B models. In each case, the model is run on a range of TPU v4 configurations. For instance, LLaMA 7B shows 4.7ms/token and 3.8ms/token on v4-8 and v4-16 respectively. For more comparison, visit the HuggingFace LLM performance leaderboard.

In the absence of the features discussed in this blog post, the LLaMA 65B running on v4-32 delivers 120ms/token instead of 14.5ms/token obtained here, leading to 8.3x speedup. As discussed earlier, developers are encouraged to try our custom torch, torch-xla wheels that unlock the repro of LLaMA inference results shared here.

Figure 1: LLaMA Inference Performance on TPU v4 hardware

PyTorch/XLA:GPU performance is better than PyTorch:GPU eager and similar to PyTorch Inductor. PyTorch/XLA:TPU performance is superior to PyTorch/XLA:GPU. In the near future, XLA:GPU will deliver optimizations that bring parity with XLA:TPU. The single A100 configuration only fits LLaMA 7B, and the 8-A100 doesn’t fit LLaMA 175B.

Figure 2: LLaMA Inference Performance on GPU A100 hardware

As the batch size increases, we observe a sublinear increase in per-token latency highlighting the tradeoff between hardware utilization and latency.

Figure 3: LLaMA Inference Performance across different batch sizes

Our studies suggest the impact of maximum sequence input length (max_seq_len) on inference latency is relatively minimal. We attribute this to the sequential and iterative nature of token generation. The small difference in performance can be due to KV cache access latency changes as the storage size increases.

Figure 4: LLaMA Inference Performance across different prompt lengths

LLMs are often memory bound applications; thus, by quantizing model parameters we enable loading and executing a larger tensor on MXUs per unit time (i.e. HBM ⇒ CMEM and CMEM ⇒ MXU data moevment). Figure 5 shows INT8 weight-only quantization offers 1.6x-1.9x speedup allowing running a larger model on a given hardware.

When BS=1, INT8 tensors are dispatched to VPU which is smaller than MXU (see the TPU v4 paper); otherwise, MXU is used. As a result, when BS=1, quantization memory bandwidth gains are offset by lack of MXU utilization. When BS>1, however, memory gains deliver superior latency on the quantized model. For example, in the case of 175B parameters LLaMA, v4-16 with quantiztion and v4-32 without quantiztion deliver similar performance. Note we do not provied FP8 comparisons because PyTorch is yet to offer this data type.

Figure 5: LLaMA Inference Performance vs. weight-only quantization. The missing blue bars suggest the model size doesn’t fit in the specified TPU hardware.

Figure 6 demonstrates the steady performance advantage of PyTorch/XLA as the input prompt length grows from 10 tokens to 1,500 tokens. This strong scaling capability suggests minimal PyTorch/XLA recompilation events enabling a wide range of real-world applications. In this experiment, the maximum length is 2,048 and maximum generation length is 256.

Figure 6: LLaMA Inference Performance vs. Input Prompt Length

Final Thoughts

We are ecstatic about what’s ahead for PyTorch/XLA and invite the community to join us. PyTorch/XLA is developed fully in open source. So, please file issues, submit pull requests, and send RFCs to GitHub so that we can openly collaborate. You can also try out PyTorch/XLA for yourself on various XLA devices including TPUs and GPUs.

Cheers,

The PyTorch/XLA Team at Google

#PoweredByPyTorch